Recall the last purchase you made from your favorite company. What comes to mind first? Is it the product's price, the perception of the product's quality, or perhaps the efficiency of the transaction? Alternatively, is it something qualitatively different, such as the memory of an experience in which you felt contentment, optimism, or peacefulness—or, perhaps sadness, worry, or even fear?

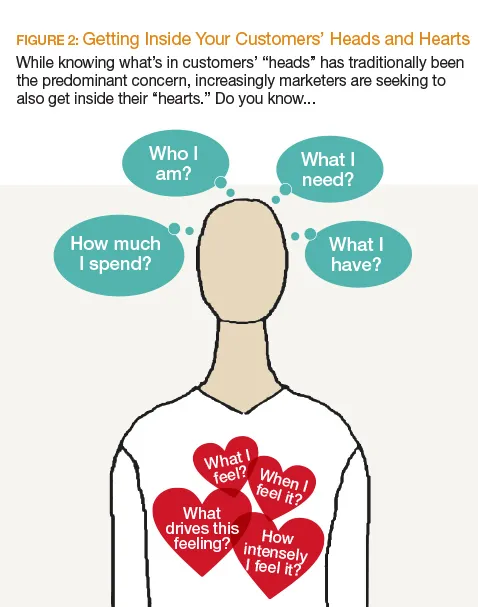

In many situations, executives have placed an emphasis on measuring and understanding the objective facets of customers' experiences with their company and its products and services. These measures often include assessments of employees' knowledge, responsiveness to customers' inquiries, and customers' waiting time for service. Yet, there is more to building a long-term, authentic and productive relationship than simply achieving operational excellence.

A positive customer experience must succeed not only in satisfying customers, but also in engendering emotions that strengthen the company-customer relationship. These affective factors, in addition to the cognitive aspects of the interaction, impact the strength of the relationship, which in turn impacts significant business outcomes such as lowering the cost to serve, increasing the likelihood to recommend, and improving the propensity for repurchase.

The rational case for emotions

Customers are not accounts, they are not records stored in a data warehouse, and they are not entries on a financial ledger. They are people. And, people feel as well as think. When a company recognizes and acts on the importance of emotions in a customer's decision, it enhances the potential for positive, "rational" results like closing the sale or gaining a referral. In fact, emotionally engaged customers across industries are known to be three times more likely to recommend that preferred brand and three times more likely to repurchase. Additionally, 44 percent of these customers report that they rarely or never shop around.1

When customers "feel good about a brand," it pays dividends. Additionally, consider that...

- Research has shown that customers' feelings of pleasure and arousal in a retail store environment predict the occurrence of spending more time in the store and of spending more money for unplanned purchases, independent of cognitive factors such as merchandise quality and variety.2

- For advertising, emotional messaging has been shown to dominate over cognitive facts in predicting purchase intent,3 and emotional advertising campaigns are twice as likely to generate large profit gains.4

- For exchanges with a high level of personal involvement such as a car purchase, the fulfillment of a customer's emotional needs (e.g., experiencing sincerity and empathy) is 40 percent more important than objective attributes such as price in the interaction.5

- Consumer emotions have been shown to predict wordof- mouth intentions, both positively and negatively.6

- Among hotel guests, the intent to return has been shown to be elevated by 41 percent for those who experience key emotions such as "respected" and "important" during their stay.7

- Based on data gathered from 10,000 consumers and across dozens of brands, research has shown that "improvements in differentiating the emotional elements of a brand yield a 50 percent greater impact on consumer loyalty than do the same improvements in differentiating a brand's functionality."8

Although marketers generally recognize the importance of customers' emotions, most still struggle to act on that understanding. Recently, a majority (62 percent) of marketers reported that rational and functional elements characterize their brand's message, with only a minority (38 percent) focusing on emotional aspects.9

If, intuitively as well as empirically, customers' emotions are understood to be so important, then why do so many companies struggle to incorporate emotions into their strategic marketing planning and into the design and delivery of their customers' experiences? The answer lies in the confusion of how best to conceptualize and classify emotions, how best to effectively measure them, and how best to realize business benefits from those insights.

Understanding emotions

In psychological and marketing literature, two dominant views of emotions have emerged. One view sees all emotions as variations of a small number of independent and underlying dimensions. These dimensions may be bipolar, ranging from negative (e.g., "I feel displeasure") to positive (e.g., "I feel pleasure"), or may be unipolar, ranging from "zero" (e.g., "I feel upbeat not at all") to positive (e.g., "I feel upbeat very strongly"). This view has the advantage of simplicity because researchers and marketers use only a few dimensions—but it also has the disadvantage of lacking specificity.

An alternative view focuses on emotions (e.g., happy or afraid) as distinct entities, each of which is assumed to have behavioral and physiological associations. The advantage of this view is that it provides a high level of granularity. Due to the use of a large number of discrete emotions, however, it has the disadvantage of increased complexity. Additionally, there is substantial disagreement among researchers on which emotions are primary and universal, and thus which emotions marketers should focus on in communications and advertisements.

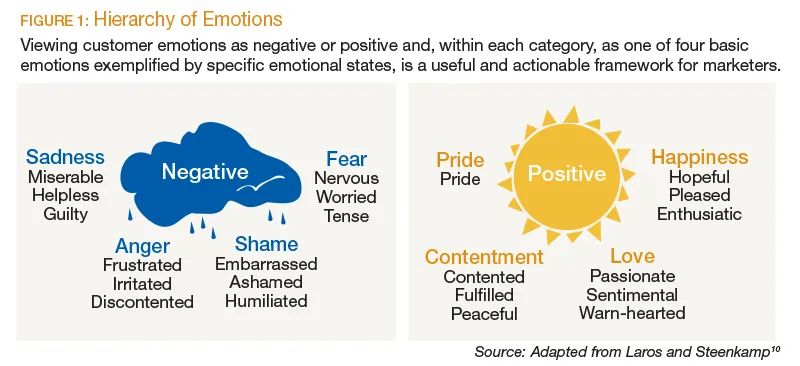

A third perspective that melds these two viewpoints organizes emotions into a three-level hierarchy (see Figure 1).11 At the highest level, emotions are separated into negative and positive categories. At the intermediate level, four positive and four negative emotions are identified. And, at the detailed level, specific emotional states are enumerated.

This structure is a useful framework for marketers, providing the simplicity as well as the comprehensiveness necessary for understanding and acting on customers' emotions. For example, a customer interaction may result in a negative experience, but how the company responds ought to be substantially different if the customer's emotion was sadness (e.g., a feeling of helplessness) versus fear (e.g., a feeling of being worried). For a feeling of helplessness, the company might appropriately try to increase the customer's perceived level of control and influence; for a feeling of worry, in contrast, the company might seek to reassure the customer.

Measuring emotions

The second challenge confronting marketers has been the measurement of emotions. Unless customers' emotions can be easily and readily identified and quantified, acting on them is prohibitively difficult. Fortunately, researchers have made progress in measuring emotions due to advancements in the disciplines of brain science, physiology, and psychology.

Our Brain and Body

One of the most fascinating developments arises from the use of functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to examine changes in brain activity associated with marketing stimuli. In one study, two groups of customers—high and low value—belonging to a department store's loyalty program were asked to indicate which one of two pieces of clothing they would purchase, identical except for the presence of different store-brand labels. Among the loyal, high-value customers, the presence of that store's brand label resulted in increased activation of the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (an area of emotional memory associated with rewards) as compared to the low-value customers. This suggests that the brand itself is a rewarding signal during a purchase decision and may contribute to sustaining an emotional attachment to the store.11

Although it provides a valuable glimpse into how customers feel and how those feelings impact purchasing behavior, fMRI is complex and expensive. Similar, but more practical, is electroencephalography (EEG), in which sensors on a headband or cap record brainwave activity in both the left and right hemispheres, and anteriorly and posteriorly. While providing less brain activation localization specificity than fMRI, it is also considerably less complex and expensive to implement. EEG has been used effectively to understand the emotional aspects of customers' experiences with advertisements and websites, as well as in-store shopping.

Finally, marketers have used biometric sensors in a band placed on the skin to monitor autonomic nervous system responses (e.g., skin conductance), increases in which are associated with emotional arousal and decreases in which are indicative of relaxation. Because the sensors are unobtrusive and portable, they can be used in a wide variety of natural settings in which a customer interacts with a company.

All of these techniques, however, only allow a marketer to understand changes in emotion at a broad level and cannot yet differentiate among specific emotions.

Our Behaviors

The expressions on customers' faces are better indicators of exactly what they are feeling. Those expressions can be codified and quantified using the Facial Action Coding System, in which visible facial muscle movements are grouped into "action units," combinations of which reveal basic emotions such as anger, disgust, enjoyment, fear, happiness, and sadness to a trained observer. By recording and examining customers' facial expressions to a stimulus (e.g., a webpage, an advertisement, or a store environment) or during an interaction, marketers can acquire insight into the underlying emotions that are evoked, such as the percentage of customers demonstrating happiness or fear. Those insights can guide product development, improvements to customers' experiences, and enhancements to customer communications and campaigns.