The Internet, mobile phones, and other emerging technologies are allowing customers to interact with businesses when and how they choose. Banking is no different. Customers are fully aware of their channel choices and are exercising them.

Data confirms this shift to multichannel banking. A survey of retail banking customers in the UK, Germany, France, and Holland reveals that European customers are increasingly using self-service channels like ATMs, Internet banking, and mobile banking.

This trend was echoed by Bank of America's decision to shrink the company's 6,100-branch network by about 10 percent by the end of 2009, a U-turn in its strategy following two decades of continuous branch expansion.

It is clear that contemporary banking customers increasingly prefer alternative channels, a trend that forces financial institutions to reconsider their channel strategy if they want to increase their shareholder value in the long run.

Customers are fully in control of the entire relationship with their service providers. They demand a smooth, personalized multichannel experience, built according to their needs, not the priorities of the business. Giving customers the multichannel options they prefer can be beneficial to the bottom line.

In a recent Peppers & Rogers Group engagement at a large bank with approximately 20 million customers and 1,000 branches, for example, we observed that customers using alternative distribution channels (ADC) are more profitable than non-ADC customers. Its retail banking ADC customers are 2.6 times more profitable than non-ADC customers; private banking ADC customers are 1.3 times more profitable. In addition, the retail customers using these channels own 2.5 more products than customers that use only the branch; private banking customers use twice as many products. There is also a positive impact on retention, as the attrition for ADC customers is less than non-ADC customers.

Not surprisingly, multichannel strategies are gaining traction in boardrooms everywhere as financial institutions worldwide recognize the advantages of multichannel migration. Unfortunately, this migration is normally done without considering the effects on the overall customer experience.

With customers in full control, providing a superior customer experience across every channel is not a "nice to have" but a "must have" with a direct impact on the bottom line. A recent Forrester Research study found that financial services customers who have a good customer experience will consider purchasing more products and services at higher levels than in other industries. They are also more reluctant to switch providers than customers in other industries. Without a customer-focused approach to multichannel strategy, banks may never get the opportunity to make the most of these potentially loyal customers.

If customers are in control, migration to alternative channels is beneficial, and the quality of the customer experience has an impact on the bottom line, what is a company to do? One answer is to manage channels through a customer-focused lens.

Channel-Centric Management: Avoid the Silos

Many financial institutions start down the migration path, but success is limited by a siloed, channel-centric focus. To make an impact, they must adopt a multichannel, customer- centric perspective where cross-channel roles and responsibilities are clearly defined across the organization. The main focus areas should be the organizational structure, ownership of the customer among channels, pricing, and implementation of cross-channel KPIs.

Organizational alternatives

Having the right organizational structure in place is mission critical when it comes to multichannel management. If the corporate structure, success metrics, and incentives are not aligned, internal conflicts will limit progress. Business units should be established or restructured in order to manage, carry, and coordinate channel-related tasks effectively. There are three basic structures for channel management within the organization:

1. Independent channel units In this structure each channel has a different team, and individual business units request actions from the related channel unit. Although it positively affects the expertise and know-how on the particular channel, customer experience across channels is easy to ignore, hampering multichannel integration efforts. Other drawbacks of this structure include overlapping requests from different channels, which increases unnecessary workload and decreases synergy between channels in terms of utilization of common resources.

2. Separate channel units under each business unit This structure establishes small channel units within each business unit that are capable of answering the particular needs of the business unit. The advantage of this structure is the elimination of the coordinating entity between business units, IT, and customers, which may easily lead to inconsistency across different customer touchpoints. Drawbacks include underdeveloped channel skills limited to the business unit's requirements, overlapping requests from different channels that increase unnecessary workload, and decreased synergy between channels in terms of utilization of common resources.

3. An independent channel management unit In this structure the channel management unit is an independent, autonomous entity that governs and coordinates the information flow between business units and the IT department. This structure brings increased efficiencies in resource utilization of different channels, development of wide know-how and expertise regarding various channels, and more effective prioritization of requests by business units. The independent unit may also create and follow a semiannual or annual plan for requested initiatives. On the other hand, an independent unit will lengthen the request process by adding an extra link in the chain as the middleman between the business units and IT department. It may also cause conflicts regarding the prioritization of requests of different business units.

Keep in mind the pros and cons of each structure, and know that the decision should be made according to the needs and conditions of each institution.

Customer ownership

Another important driver of success for customer-centric channel management is the responsibility for the "ownership" of the customer relationship among channels.

Institutions can choose between different ownership structures, varying from a single-channel-centric model to an independent ownership model.

The first model gives the ownership to a single channel, in most cases the branch, as a result of the historical and physical weight of the channel, where the second model provides freedom of each channel to become a profit center by owning its own customers.

Executives need to consider their institutions' specific conditions before deciding on a model. Both models have benefits and risks. For example, the first model lacks incentives for other channels to consider profitability as they are positioned mostly in a supporting role, while the second model opens the door for cannibalization as a result of the competition between channels.

One best practice example is that of a large retail bank in EMEA with 15 million customers. Since many customers have a relationship with multiple branches, the bank uses a list of ranked criteria to determine which branch owns the customer. It created the discipline to determine customer ownership annually with five factors:

- Largest credit balance

- Largest debit balance

- Largest number of products

- Highest number of transactions

- Where the customer first opened an account

The ownership is defined by the order above, and the owner of the customer is the branch regardless of the fact that the customer uses other channels such as the Web more than a branch. This is a best practice in itself for similar institutions because this particular bank has always been a branch-centric organization and in parallel follows a corporate strategy that places branches in the center.

Pricing alternatives

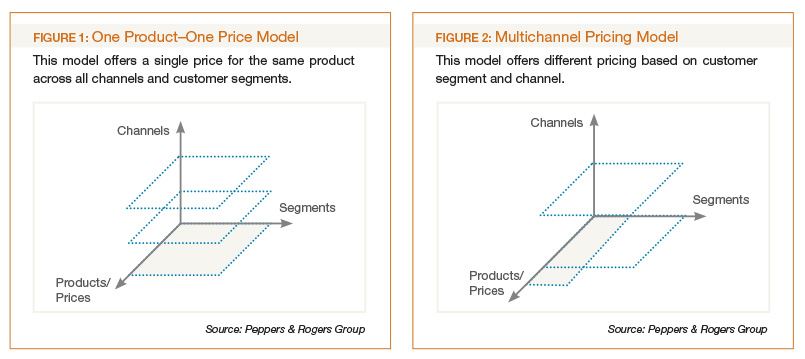

Channel pricing is also an important component of customer- centric channel management. Although one can adopt a number of hybrid structures, two major models emerge in the industry, similar to the customer ownership models: one product–one price model versus multichannel pricing. The one product–one price model adopts a straightforward approach where there is only a single price for the same product across all channels regardless of the customer segment (see Figure 1). A customer applying for a personal loan receives the same rate at the branch compared to online channels. The model is mostly applicable where branches are the focal point of the strategy. However, it does not address customers' different needs because it does not differentiate between customer segments and channels.

The multichannel pricing model suggests different pricing by customer segment and channel (see Figure 2). A customer applying for a personal loan can receive a different rate based on the channel of application and her segment. As the ultimate customer-centric model for pricing, it brings a risk of causing cannibalization among channels, as well as increased complexity for managing costs.

Setting the right KPIs

Consumers select different channels for different purposes, such as gathering information, seeking product advice, or completing a sales transaction, which makes it difficult to measure channel performance accurately. In order to ensure accurate channel performance management, banks should consider three key metrics:

- Identification of customer channel segments

- Identification of channel revenues and costs by channel segment

- Calculation of true conversion rates across channels

Customers may display different channel usage behavior depending on the type of channel, products, and services offered on channels. Some customers may gather information about a product from the website (say investment funds), go to the branch and ask for advice about which fund to purchase, and then go home and call the contact center to make a purchase after evaluating the product with their spouses. In this case the customer is a hybrid customer regarding channel usage and there might be non-hybrid customers who are using only the branch or only the website for all their needs. After identifying channel segments, banks can calculate the contribution of each segment to the total revenue and costs incurred for each channel. This information can be used to set more clear and effective channel targets.

As consumers increase their use of multiple channels even when doing a single transaction, the contribution of a channel to the organization's sales activities cannot be measured by looking only at the number of total sales transactions completed on that particular channel.

In this respect, before setting KPIs on channel profitability and calculating the marginal contribution of each sale on a specific channel, the true sales contribution rate must be measured. In this case, a specific percentage of the actual sales would be allocated separately if any of the inquiry or initiation steps occur from a different channel than the sales origination channel. The task of measuring this rate might prove to be difficult as it is not an easy task to identify, record, and track each and every customer transaction across all channels. For better performance management, this measure should be estimated and put in place.

It should be reemphasized that there is no ideal approach to multichannel strategy, and each institution should consider its own reality in terms of corporate strategy, business model, and customer behavior in order to tailor its own approaches and meet the unique needs of its customers.